William Collins

An imprint of HarperCollinsPublishers

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

WilliamCollinsBooks.com

This eBook first published in Great Britain by William Collins in 2018

Copyright © 2018 by Smithsonian Institution

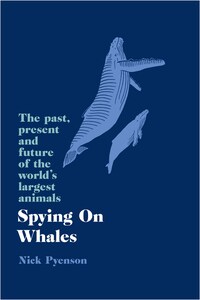

Illustrations © 2017 Alex Boersma

Cover illustrations by Alex Boersma

First published in the United States of America by Viking, an imprint of Penguin Random House LLC in 2018 as Spying on Whales: The Past, Present, and Futureof Earth’s Most Awesome Creatures

The author asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work.

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on-screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, down-loaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins.

Source ISBN: 9780008244460

Ebook Edition © June 2018 ISBN: 9780008244484

Version: 2018-06-04

Every author writes with a very specific reader in mind.

I wrote this book for you.

And for my family.

What have we been doing all these centuries but trying to call God back to the mountain, or, failing that, raise a peep out of anything that isn’t us? What is the difference between a cathedral and a physics lab? Are not they both saying: Hello? We spy on whales and on interstellar radio objects; we starve ourselves and pray till we’re blue.

—Annie Dillard, Teaching a Stone to Talk

For the animal shall not be measured by man. In a world older and more complete than ours, they move finished and complete, gifted with the extension of the senses we have lost or never attained, living by voices we shall never hear. They are not brethren, they are not underlings: they are other nations, caught with ourselves in the net of life and time, fellow prisoners of the splendour and travail of the earth.

—Henry Beston, The Outermost House

At this very moment, two spacecraft move at over thirty-four thousand miles per hour, about ten billon miles away from us, each carrying a gold-plated copper record. The spacecraft, Voyager 1 and Voyager 2, are meant as messengers: they carry information about our address in the solar system, the building blocks of our scientific knowledge, and a small sampling of images, music, and greetings from around the world. They also carry whalesong.

The long squeaks and moans on the record belong to humpback whales. In the 1970s, when the Voyager mission launched, our view of whales was rapidly changing, from game animals to cultural icons and symbols of a nascent environmental movement. Scientists had recently discovered that male humpbacks produce complex songs, composed of phrases collected under broader themes, nested like Russian dolls that repeat in a loop. Humpback whalesong has evolved even since we started listening as each new singer improvises on the loop, creating new structures and hierarchies that constantly change over years, and across ocean basins.

Whalesong, however, remains a riddle to anyone who isn’t a humpback whale. We can capture its variation, details, and complexity, but we don’t know what any of it truly means. We lack the requisite context to decipher and understand it—or, really, any part of cetacean culture. Even so, we send whalesong into interstellar space because the creatures that sing these songs are superlative beings that fill us with awe, terror, and affection. We have hunted them for thousands of years and scratched them into our mythologies and iconography. Their bones frame the archways of medieval castles. They’re so compelling that we imagine aliens might find them interesting—or perhaps understand their otherworldly, ethereal song.

In the meantime, whales here on Earth remain mysterious. They live 99 percent of their lives underwater, far away from continuous contact with people and beyond most of our observational tools. We tend to think about them only when we glimpse them from the safety of a boat, or when they wash up along our shores. They also have an evolutionary past that is surprising and incompletely known. For instance, they haven’t always been in the water. They descend from ancestors that lived on land, more than fifty million years ago. Since then, they transformed from four-limbed riverbank dwellers to oceangoing leviathans, in a chronicle we can read only from their fossil record, a puzzle of bone shards unevenly spread across the globe.