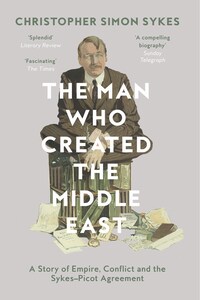

The Man Who Created the Middle East: A Story of Empire, Conflict and the Sykes-Picot Agreement

At the age of only 36, Sir Mark Sykes was signatory to the Sykes-Picot agreement, one of the most reviled treaties of modern times. A century later, Christopher Sykes’ lively biography of his grandfather reassesses his life and work, and the political instability and violence in the Middle East attributed to it.The Sykes-Picot agreement was a secret pact drawn up in May 1916 between the French and the British, to divide the collapsing Ottoman Empire in the event of an allied victory in the First World War. Agreed without any Arab involvement, it negated an earlier guarantee of independence to the Arabs made by the British. Controversy has raged around it ever since.Sir Mark Sykes was not, however, a blimpish, ignorant Englishman. A passionate traveller, explorer and writer, his life was filled with adventure. From a difficult, lonely childhood in Yorkshire and an early life spent in Egypt, India, Mexico, the Arabian desert, all the while reading deeply and learning languages, Sykes published his first book about his travels through Turkey aged only twenty. After the Boer War, he returned to map areas of the Ottoman Empire no cartographer had yet visited. He was a talented cartoonist, excellent mimic and amateur actor, gifts that ensured that when elected to parliament a full House of Commons would assemble to listen to his speeches.During the First World War, Sykes was appointed to Kitchener’s staff, became Political Secretary to the War Cabinet and a member of the Committee set up to consider the future of Asiatic Turkey, where he was thirty years younger than any of the other members. This search would dominate the rest of his life. He was unrelenting in his pursuit of peace and worked himself to death to find it, a victim of both exhaustion and the Spanish Flu.Written largely based on the previously undisclosed family letters and illustrated with Sykes' cartoons, this sad story of an experienced, knowledgeable, good-humoured and generous man once considered the ideal diplomat for finding a peaceful solution continues to reverberate across the world today.