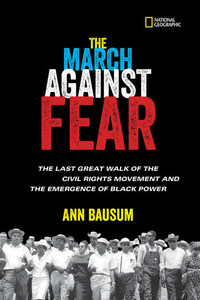

“There is nothing

more powerful

to dramatize an injustice

like the

tramp,

tramp,

tramp

of marching feet.”

Martin Luther King, Jr., June 7, 1966, at a rally in

Memphis, Tennessee, during the March Against Fear

THE LAST GREAT WALK OF THE CIVIL RIGHTS MOVEMENT AND THE EMERGENCE OF BLACK POWER

![]()

Countless supporters joined James Meredith (center, wearing pith helmet and grasping walking stick) for the final hike of the March Against Fear, June 26, 1966, to the Mississippi State Capitol in Jackson, including civil rights movement leaders Martin Luther King, Jr. (left of Meredith, arm linked with wife Coretta), Stokely Carmichael (right of Meredith, wearing overalls), and Floyd McKissick (right of Carmichael). Credit 1

![]()

Copyright © 2017 Ann Bausum

All rights reserved. Reproduction of the whole or any part of the contents without written permission from the publisher is prohibited.

Since 1888, the National Geographic Society has funded more than 12,000 research, exploration, and preservation projects around the world. The Society receives funds from National Geographic Partners LLC, funded in part by your purchase. A portion of the proceeds from this book supports this vital work. To learn more, visit www.natgeo.com/info.

For more information, visit nationalgeographic.com, call 1-800-647-5463, or write to the following address:

National Geographic Partners

1145 17th Street N.W.

Washington, D.C. 20036-4688 U.S.A.

Visit us online at nationalgeographic.com/books

For librarians and teachers: ngchildrensbooks.org

More for kids from National Geographic: kids.nationalgeographic.com

For rights or permissions inquiries, please contact National Geographic Books Subsidiary Rights: bookrights@natgeo.com

NATIONAL GEOGRAPHIC and Yellow Border

Design are trademarks of the National Geographic Society, used under license.

Cover Design by James Hiscott, Jr.

Text set in Baskerville MT Std, Univers

Display text set in Veneer, Univers

Hardcover ISBN 9781426326653

ISBN 9781426326660

Ebook ISBN 9781426326684

v4.1

a

Version: 2017-07-05

FOR THE MARCHERS THEN, NOW, AND ALWAYS.

—AB

Readers will travel through history with this book and encounter examples of language old and new, respectful and hateful. In my text, I use the terms “black” and “African American” interchangeably and with equal respect. The widespread use of the word “Negro” in quotations from historical source material should be viewed within the context of the times as a term of respect, too. Racial epithets of that era remain no less offensive today, but they are a part of the historical record and are presented in quotations from the period without censorship.

—Ann Bausum

One minute James Meredith was walking along a rural road in Mississippi, two days into an estimated two-week-long journey to the state capital of Jackson. The next minute a stranger had climbed out of the roadside honeysuckle and started shooting at him.

The first blast from the 16-gauge shotgun spewed tiny balls of ammunition toward the hiker, but the pellets struck the pavement nearby, not Meredith himself.

Undeterred, the gunman fired again.

BLAM!

Some pellets found their mark.

BLAM!

Shotgun pellets from the third blast penetrated Meredith’s scalp, neck, shoulder, back, and legs. His hiking companions seemed frozen in place, transfixed by shock and unable to react to the sudden threat.

Meredith had cried out in surprise when the shooting began. Then he, like those walking with him, began searching for cover. He dragged himself across the pavement, trying to put distance between himself and his attacker. He collapsed on his side, sprawled upon the grassy shoulder of U.S. Highway 51, his blood oozing from multiple wounds into the red soil of Mississippi.

The penetration of countless tiny balls of shot through his skin left Meredith moaning in pain. “Get a car and get me in it,” he implored the others at the scene. An ambulance arrived quickly, and within minutes Meredith was being raced back along his hiking route, bound for a Memphis hospital. Emergency room physicians concluded that his wounds were not life-threatening, although they could have been if the shooter had been closer or his aim more accurate.

![]()

James Meredith collapsed in the road after he was ambushed and shot in rural Mississippi on June 6, 1966. Credit 2

Doctors shaved the back of Meredith’s head and dug as many as 70 pellets out of his scalp, back, limbs, even from behind an ear, before they questioned their effort. Although only a fraction of the 450 or so shotgun pellets fired toward Meredith had found their mark, countless balls of shot remained embedded in his flesh. Yet it was so time-consuming—and so painful—to remove them, that doctors decided to leave the rest alone. He wouldn’t be the first person to walk around with bird shot under his skin. Soon after, a local news reporter found a medical resident familiar with the case and asked him about the patient’s condition. The doctor-in-training replied with a candor that, although shocking today, would have seemed unremarkable at that time in the South. “If he had been an ordinary nigger on an ordinary Saturday night,” the man observed, “we’d have swabbed his ass with merthiolate [an antiseptic] and sent him home”