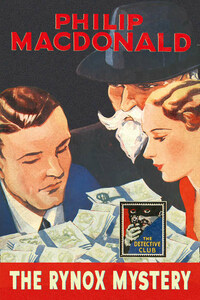

‘THE DETECTIVE STORY CLUB is a clearing house for the best detective and mystery stories chosen for you by a select committee of experts. Only the most ingenious crime stories will be published under the THE DETECTIVE STORY CLUB imprint. A special distinguishing stamp appears on the wrapper and title page of every THE DETECTIVE STORY CLUB book—the Man with the Gun. Always look for the Man with the Gun when buying a Crime book.’

Wm. Collins Sons & Co. Ltd., 1929

Now the Man with the Gun is back in this series of COLLINS CRIME CLUB reprints, and with him the chance to experience the classic books that influenced the Golden Age of crime fiction.

COLLINS CRIME CLUB

An imprint of HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

www.harpercollins.co.uk

First published for The Crime Club by W. Collins Sons & Co. Ltd 1932

Copyright © Estate of Philip MacDonald 1932

Introduction © Estate of Julian Symons 1980

A catalogue copy of this book is available from the British Library.

This novel is entirely a work of fiction. The names, characters and incidents portrayed in it are the work of the author’s imagination. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events or localities is entirely coincidental.

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, down-loaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins.

Source ISBN: 9780008216375

Ebook Edition © December 2016 ISBN: 9780008216382

Version: 2016-11-23

THE idea of the crime story in which the solution should be the result of perfectly rational deductions from given facts—an exercise in ratiocination, as Poe called it—was one that preoccupied writers in the ’twenties and early ’thirties, when the crime story was coming of age. It was this dream that the early Ellery Queen books tried to fulfil with their ‘Challenge to the Reader’ three-quarters of the way through; that was at the heart of John Dickson Carr’s locked room mysteries; that was approached at times by writers as various as Anthony Berkeley, Agatha Christie and C. Daly King.

The Maze, which was published in 1932, is Philip MacDonald’s contribution to this conception of the totally logical puzzle. It is, he says, ‘An Exercise in Detection’, and he claims that you are provided with all the evidence on which his detective, Anthony Gethryn, works, and from which he deduces the truth. He says more than this:

In this book I have striven to be absolutely fair to the reader. There is nothing—nothing at all—for the detective that the reader has not had. More, the reader has had his information in exactly the same form as the detective—that is, the verbatim report of evidence and question.

This is a fair story.

Does Philip MacDonald claim too much? I don’t think so. The facts are clearly laid out, and Gethryn’s deductions are admirably logical, beginning with what he calls oddities, and moving from one of these to another to build a case which—if we had spotted the oddities—we could have formulated ourselves. Upon the basis of logic, Gethryn’s case is not to be denied, although, as he acknowledges, it is a structure that can be demonstrated but not proved. A perfect crime story, then? Why no, for The Maze has the weakness inherent in that desire for a wholly logical crime story, the weakness that we take an interest in the solution to the crime but not in the people who may have committed it. Yet in its time The Maze was a notable and underrated crime story, and it remains one of the truly original experiments of the period.

Today Philip MacDonald is almost forgotten, but he and his detective Anthony Gethryn were celebrated figures in the years between the Wars. The Rasp, the first crime story he published under his own name, was an immediate success, and The Noose (he had a taste for single word titles) was the first Crime Club choice in 1930. The Evening Standard bought the serial rights, MacDonald’s sales quadrupled, and within a year the Crime Club had 200,000 members. MacDonald continued to produce successful books under several pseudonyms and a number of them were experimental in one way or another. Three of the best were Rynox, Murder Gone Mad, and X v Rex, the last of which was written under the pseudonym of Martin Porlock. The construction of these books is sometimes careless, but they all contain extremely ingenious ideas, and the desire to do something new is always apparent. Then, in the early ’thirties, MacDonald was invited to Hollywood by RKO Pictures, became a scriptwriter, and wrote little more except for the screen, although he produced in 1952 a collection of short stories called