Published by HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd

1 London Bridge Street

London, SE1 9GF

www.harpercollins.co.uk

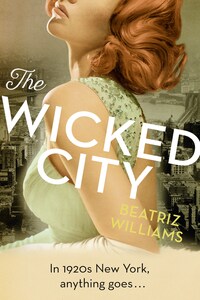

First published by Putnam, Penguin USA 2014

First published in the UK by HarperCollinsPublishers 2017

Copyright © Beatriz Williams 2014

Cover design by TBC © HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd 2017

Cover photographs © TBC

Beatriz Williams asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work.

A catalogue copy of this book is available from the British Library.

This novel is entirely a work of fiction. The names, characters and incidents portrayed in it are the work of the authorâs imagination. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events or localities is entirely coincidental.

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, down-loaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins.

Source ISBN: 9780399162176

Ebook Edition © December 2017 ISBN: 9780008134983

Version: 2017-08-18

In the summer of 1914, a beautiful thirty-eight-year-old American divorcée named Caroline Thompson took her twenty-two-year-old son, Mr. Henry Elliott, on a tour of Europe to celebrate his recent graduation from Princeton University.

The outbreak of the First World War turned the family into refugees, and according to legend, Mrs. Thompson ingeniously negotiated her own fair person in exchange for safe passage across the final border from Germany.

A suitcase, however, was inadvertently left behind.

In 1950, the German government tracked down a surprised Mr. Elliott and issued him a check in the amount of one hundred deutsche marks as compensation for âlost luggage.â

This is not their story.

I nearly missed that card from the post office, stuck up as it was against the side of the mail slot. Just imagine. Of such little accidents is history made.

Iâd moved into the apartment only a week ago, and I didnât know all the little tricks yet: the way the water collects in a slight depression below the bottom step on rainy days, causing you to slip on the chipped marble tiles if you arenât careful; the way the butcherâs boy steps inside the superintendentâs apartment at five-fifteen on Wednesday afternoons, when the superâs shift runs late at the cigar factory, and spends twenty minutes jiggling his sausage with the superâs wife while the chops sit unguarded in the vestibule.

Andâthis is important, nowâthe way postcards have a habit of sticking to the side of the mail slot, just out of view if youâre bending to retrieve your mail instead of crouching all the way down, as I did that Friday evening after work, not wanting to soil my new coat on the perpetually filthy floor.

But luck or fate or God intervened. My fingers found the postcard, even if my eyes didnât. And though I tossed the mail on the table when I burst into the apartment and didnât sort through it all until late Saturday morning, wrapped in my dressing gown, drinking a filthy concoction of tomato juice and the-devil-knew-what to counteract the several martinis and one neat Scotch Iâd drunk the night before, not even I, Vivian Schuyler, could elude the wicked ways of the higher powers forever.

Mind you, Iâm not here to complain.

âWhatâs that?â asked my roommate, Sally, from the sofa, such as it was. The dear little tart appeared even more horizontally inclined than I did. My face was merely sallow; hers was chartreuse.

âCard from the post office.â I turned it over in my hand. âThereâs a parcel waiting.â

âFor you or for me?â

âFor me.â

âWell, thank God for that, anyway.â

I looked at the card. I looked at the clock. I had twenty-three minutes until the post office on West Tenth Street closed for the weekend. My hair was unbrushed, my face bare, my mouth still coated in a sticky film of hangover and tomato juice.

On the other hand: a parcel. Who could resist a parcel? A mysterious one, yet. All sorts of brown-paper possibilities danced in my head. Too early for Christmas, too late for my twenty-first birthday (too late for my twenty-second, if youâre going to split hairs), too uncharacteristic to come from my parents. But there it was, misspelled in cheap purple ink: