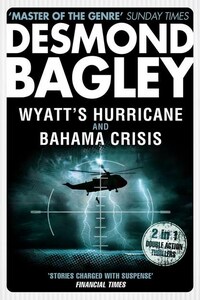

The Super-Constellation flew south-east in fair weather, leaving behind the arc of green islands scattered across the crinkled sea, the island chain known as the Lesser Antilles. Ahead, somewhere over the hard line of the Atlantic horizon, was her destination – a rendezvous with trouble somewhere north of the Equator and in that part of the Atlantic which is squeezed between North Africa and South America.

The pilot, Lieutenant-Commander Hansen, did not really know the exact position of contact nor when he would get there – he merely flew on orders from a civilian seated behind him – but he had flown on many similar missions and knew what was expected of him, so he relaxed in his seat and left the flying to Morgan, his co-pilot. The Lieutenant-Commander had over twelve years’ service in the United States Navy and so was paid $660 a month. He was grossly underpaid for the job he was doing.

The aircraft, one of the most graceful ever designed, had once proudly flown the North Atlantic commercial route until edged out by the faster jets. So she had been put in mothballs until the Navy had need of her and now she wore United States Navy insignia. She looked more battered than seemed proper in a Navy plane – the leading edge of her wings was pitted and dented and the mascot of a winged cloud painted on her nose was worn and abraded – but she had flown more of these missions than her pilot and so the wear and tear was understandable.

Hansen looked at the sky over the horizon and saw the first faint traces of cirrus flecking the pale blue. He flicked a switch and said, ‘I think she’s coming up now, Dave. Any change of orders?’

A voice crackled in his earphones. ‘I’ll check on the display.’

Hansen folded his arms across his stomach and stared ahead at the gathering high clouds. Some Navy men might have resented taking instructions from a civilian, especially from one who was not even an American, but Hansen knew better than that; in this particular job status and nationality did not matter a damn and all one needed to know was that the men you flew with were competent and would not get you killed – if they could help it.

Behind the flight deck was the large compartment where once the first-class passengers sipped their bourbon and joshed the hostesses. Now it was crammed with instruments and men; consoles of telemetering devices were banked fore and aft, jutting into promontories and forming islands so that there was very little room for the three men cramped into the maze of electronic equipment.

David Wyatt turned on his swivel stool and cracked his knee sharply against the edge of the big radar console. He grimaced, reflecting that he would never learn, and rubbed his knee with one hand while he switched on the set. The big screen came to life and shed an eerie green glow around him, and he observed it with professional interest. After making a few notes, he rummaged in a satchel for some papers and then got up and made his way to the flight deck.

He tapped Hansen on the shoulder and gave the thumbs-up sign, and then looked ahead. The silky tendrils of the high-flying cirrus were now well overhead, giving place to the lower flat sheets of cirrostratus on the horizon, and he knew that just over the edge of the swelling earth there would be the heavy and menacing nimbostratus – the rain-bearers. He looked at Hansen. ‘This is it,’ he said, and smiled.