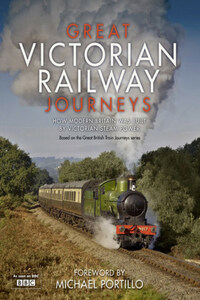

On an engine from the Downpatrick Heritage Steam Railway.

ince 2009, when I started making televised train journeys using Bradshawâs Handbook, I have tried to imagine what impact and impression the arrival of the railways made on British society. Of course every generation since has experienced technological change, which has, if anything, grown faster. As we look back over twenty years, most of us can no longer understand how we lived without mobile phones and the internet. Similarly, a Victorian by the 1850s must have struggled to recall the days when he or she had had to travel by coach, never able to exceed the speed of a horse. There had been a revolution in communications, perhaps similar in scope to the one that we are experiencing today.

But on top of that, Britain underwent a physical metamorphosis. Where before, country lanes meandered, now embankments, tunnels and viaducts scythed through the landscape. Stations sprouted up, resembling Italian palaces, French châteaux or even Gothic cathedrals. Fearsome locomotives belching fire and steam frightened the horses as they sliced through city centres, or engulfed fields in flame as stray sparks set light to hay or stubble.

I remember being in awe and fear of steam locomotives. They were so big and noisy. Their wheels towered above me (especially when I was a boy, of course) and they were given to highly unpredictable behaviour, suddenly releasing clouds of water vapour with a hiss that made me jump. How did the Victorian middle classes in their finery, how did genteel ladies, cope with their sudden proximity to these roaring fireboxes, with being brought face to face with the industrial revolution?

How could they adapt to speed? At the Rainhill trials to choose a source of traction for the Manchester to Liverpool railway, Stephensonâs Rocket reached 30 miles per hour, a velocity previously unseen and hard even to imagine. The potency of the technology took some getting used to. At the inauguration of that line in 1830, William Huskisson MP, former President of the Board of Trade, left his carriage to greet the Prime Minister, the Duke of Wellington. The Rocket, running on the parallel track, struck him as he tried to scramble out of its path. A train transported him to the vicarage at Eccles where he died of his injuries.

When Isambard Kingdom Brunel opened his epic Box tunnel on the Great Western Railway, Dionysius Lardner, a professor of astronomy, was on hand to warn that if the brakes failed the train would accelerate and the passengers suffocate; and some at least believed him and alighted before the tunnel to continue their journey by more traditional means.

At the beginning of the nineteenth century William Blake wrote of âdark Satanic Millsâ. The railways greatly accelerated the industrial revolution. George Bradshaw was enthusiastic about the railways, and the Handbook describes with admiration the dimensions of stations, tunnels and bridges. But the bookâs depictions of iron-smelting furnaces lighting up the night sky sometimes bring the fires of Hell to mind. Bradshawâs awareness of the social consequences of the industrial revolution suggests that Victorians saw that progress had brought both paradise and inferno.

Of Merthyr Tydfil the Handbook says:

Visitors should see the furnaces by night, when the red glare of the flames produces an uncommonly striking effect. Indeed, the town is best visited at that time, for by day it will be found dirty ... Cholera and fever are of course at home here ... We do hope that proper measures will be taken by those who draw enormous wealth from these [iron and coal] works to improve the condition of the people.

Quakers like Bradshaw tended to believe strongly that the industrialist owed a duty of care to his workers and their families.

To judge from the Great Western works at Swindon, railway magnates were appropriately paternalistic, housing the employees in model dwellings and supplying free rail travel for a family summer holiday in Devon or Cornwall. Many thousands would depart on charter trains, turning Swindon for a week into a virtual ghost town.

Train travel vastly broadened the horizons of working-class people. The mid-nineteenth century saw an enormous growth in travel and in resorts. As the railway navvies levelled the land, the railways levelled society. Those of modest means, who before train travel might scarcely have travelled beyond a 15-mile radius of home, could leave the smoke and grime of city life and enjoy the âsalubriousâ (to use a favourite Bradshaw word) sea or mountain air. Town dwellers could for the first time enjoy fresh sea fish and a range of perishable farm products.